Difference between revisions of "Worked Examples"

Pinventado (talk | contribs) (Refined context to highlight a students' learning state) |

Pinventado (talk | contribs) (Replace author with contributor) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox_designpattern | {{Infobox_designpattern | ||

|image=Worked_examples.png | |image=Worked_examples.png | ||

| | |contributor=[[User:Pinventado|Paul Inventado]], Peter Scupelli | ||

|dataanalysis=[[Analysis:Student_affect_and_interaction_behavior_in_ASSISTments#hintusage |Student affect and interaction behavior in ASSISTments]] | |dataanalysis=[[Analysis:Student_affect_and_interaction_behavior_in_ASSISTments#hintusage |Student affect and interaction behavior in ASSISTments]] | ||

|domain= General | |domain= General | ||

Revision as of 11:56, 6 November 2015

| Worked Examples | |

| Contributors | Paul Inventado, Peter Scupelli |

|---|---|

| Last modification | November 6, 2015 |

| Source | {{{source}}} |

| Pattern formats | OPR Alexandrian |

| Usability | |

| Learning domain | General |

| Stakeholders | Teachers, Students |

| Production | |

| Data analysis | Student affect and interaction behavior in ASSISTments |

| Confidence | |

| Evaluation | eLearning Papers review PLoP 2015 writing workshop Talk:ASSISTments |

| Application | ASSISTments |

| Applied evaluation | ASSISTments |

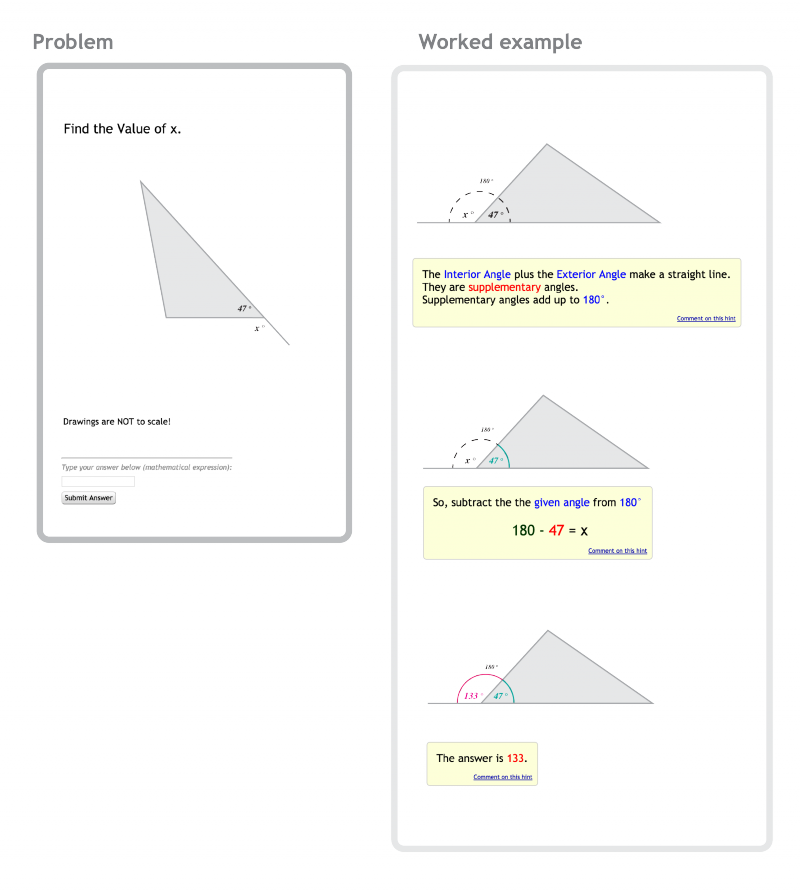

If a student doesn’t have an overview of how to solve the problem and where to begin, then provide a worked example so that students can have an overview of the procedures to follow.

Context

Teachers ask their students to answer exercises on an online learning system that help them practice what they learned in class, and assess their understanding. Teachers design and encode the problems with corresponding answers in the system. Teachers also design feedback such as hints, or bug messages (i.e., short explanation why the answer was incorrect) to address common student misconceptions or errors. When students get stuck or have a difficult time solving the problem, they can request for help from the system and the system gives back the encoded teacher feedback.

Problem

Some students don’t have an overview of how to solve the problem and where to begin.

Forces

- Prior knowledge. Students may find it impossible to solve a problem when they have not acquired the necessary skills to solve it[1].

- Randomness. When students do not know how to solve a problem, they randomly combine elements they already know to form a solution and test its effectiveness. Although it is possible to find a solution this way, it could take a lot of time and effort especially if it is a complex problem[1]).

- Affective entry. When students are unable to achieve their learning goals, they may become frustrated, discouraged of their abilities, and dislike the subject[2].

- Limited resources. Student attention and patience is a limited resource possibly affected by pending deadlines, upcoming tests, achievement in previous learning experiences, personal interest, quality of instruction, achievement in previous learning experiences, personal interest, quality of instruction, and others[3][2].

Solution

Therefore, provide a worked example so that students can have an overview of the procedures to follow.

Students may request for a worked example themselves, or the system could show the worked example automatically according to different mechanisms (e.g., too many attempts, predictions of student ability to solve the problem).

Consequences

Benefits

- Worked examples help students form new knowledge, which they can use to solve similar problems.

- Students see an effective solution to adapt instead of finding solutions on their own.

- Students will be more confident in their abilities and develop interest in the subject when they successfully apply the solution.

- Students will be focused in activities they know how to perform.

Liabilities

- Teachers and content experts will need to provide worked examples aside from hints and other feedback.

- The online learning system will need to provide an interface to show worked examples.

Evidence

Literature

Learning from examples is a common learning strategy that students use to acquire new skills. Worked examples give a step-by-step demonstration of how to perform a task or solve a problem. It helps novice learners form basic knowledge structures, which they can use to acquire new knowledge and skills through practice[4].

Discussion

In a meeting with Ryan Baker and his team at Teacher's College in Columbia University, Neil Heffernan and his team at Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and Peter Scupelli and his team at the School of Design in Carnegie Mellon University (i.e., ASSISTments stakeholders), the team agreed that linking to external content such as textbooks was a notable, recurring design problem. They also considered consolidating content in ASSISTments as a good solution.

David West, the pattern's shepherd at PLoP 2015, also considered the pattern definition acceptable.

Data

According to an analysis of ASSISTments’ data, students rapidly requested for all available hints when they did not know how to solve the problem (i.e., based on hint request and answer correctness features). Students could have used hints as a proxy for worked examples, which showed them the entire procedure for solving the problem.

Related patterns

Worked examples organize the solution into a series of steps much like Wizard[5].

Example

When teachers create a math problem in an online learning system, they can encode the math problem, the correct answer, corresponding hints, and also a worked example. Students can request for worked examples to see an effective solution they can learn from, and use it to solve the current problem and similar problems in the future.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sweller, J. (2004). Instructional design consequences of an analogy between evolution by natural selection and human cognitive architecture. Instructional science, 32(1-2), 9-31.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bloom, B. S. (1974). Time and learning. American psychologist, 29(9), 682.

- ↑ Arnold, A., Scheines, R., Beck, J. E., and Jerome, B. (2005). Time and attention: Students, sessions, and tasks. In Proceedings of the AAAI 2005 Workshop Educational Data Mining (pp. 62-66).

- ↑ Clark, R. C., and Mayer, R. E. (2011). E-learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Tidwell, J. (2011). Designing Interfaces. O’Reilly Media, Sebastapool, CA, USA.